The novel centers upon the Ogata family of Kamakura, and its events are witnessed from the perspective of its aging patriarch, Shingo, a businessman close to retirement who works in Tokyo.

Although only sixty-two years old at the beginning of the novel, Shingo has already begun to experience temporary lapses of memory, to recall strange and disturbing dreams upon waking, and occasionally to hear sounds heard by no one else, including the titular noise which awakens him from his sleep one night, "like wind, far away, but with a depth like a rumbling of the earth." Shingo takes the sound to be an omen of his impending death, as he had once coughed up blood (a possible sign of tuberculosis) a year before, but had not sought medical consultation and the symptom subsequently went away.

Although he does not outwardly change his daily routine, Shingo begins to observe and question more closely his relations with the other members of his family, who include his wife Yasuko, his philandering son Shuichi (who, in traditional Japanese custom, lives with his wife in his parents' house), his daughter-in-law Kikuko, and his married daughter Fusako, who has left her husband and returned to her family home with her two young daughters. Shingo realizes that he has not truly been an involved and loving husband and father, and perceives the marital difficulties of his adult children to be the fruit of his poor parenting.

To this end, he begins to question his secretary, Tanizaki Eiko, about his son's affair, as she knows Shuichi socially and is friends with his mistress, and he quietly puts pressure upon Shuichi to quit his infidelity.

At the same time, he uncomfortably becomes aware that he has begun to experience a fatherly yet erotic attachment to Kikuko, whose quiet suffering in the face of her husband's unfaithfulness, physical attractiveness, and filial devotion contrast strongly with the bitter resentment and homeliness of his own daughter, Fusako.

Complicating matters in his own marriage is the infatuation that as a young man he once possessed for Yasuko's older sister, more beautiful than Yasuko herself, who died as a young woman but who has again begun to appear in his dreams, along with images of other dead friends and associates.

The novel may be interpreted as a meditation uponaging and its attendant decline, and the coming to terms with one's mortality that is its hallmark. Even as Shingo regrets not being present for his family and blames himself for his children's failing marriages, the natural world, represented by the mountain itself, the cherry tree in the yard of his house, the flights of birds and insects in the early summer evening, or two pine trees he sees from the window of his commuter train each day, comes alive for him in a whole new way, provoking meditations on life, love, and companionship.

51. Nikos Kazantzakis, Greece, (1883-1957), Zorba the Greek

Zorba the Greek is a 1964 movie by Michael Cacoyannis, originally titled Alexis Zorbas, based on the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis.

Anthony Quinn, who was not Greek but Mexican American,played the title character in what may very well be his most memorable role as an earthy and the Akrotiri peninsula. The famous scene in which Anthony Quinn dances the Sirtaki was shot on the beach of the village of Stavros.

The movie won three Oscars:

- Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress - Lila Kedrova

- Academy Award for Best Art Direction- Set Decoration, Black-and-White - Vassilis Fotopoulos

- Academy Award for Best Cinematography - Black-and-White - Walter Lassally - Oscar is shown in tavern Christiana, Stavros

The movie was shot on location on the Greek island of Crete. Specific places of Crete featured include the town of Chania, theApokoronas region for best actor in a leading role and Michael Cacoyannis received three nominations for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium.

52. D.H. Lawrence, England, (1885-1930), Sons and Lovers

(links để đọc tiểu thuyê´t này

http://classicreader.com/booktoc.php/sid.1/bookid.903/)

Sons and Lovers is the third published novel of D.H. Lawrence, taken by many to be his earliest masterpiece. It tells the story of Paul Morel, a young man and a budding artist. This autobiographical novel is a brilliant evocation of life in a working class mining community.

The original 1913 edition was heavily edited by Edward Garnett who removed eighty passages, roughly a tenth of the text. Despite this the novel is dedicated to Garnett. It was not until the 1992Cambridge University Pressedition that the missing text was restored.

Lawrence rewrote the work four times until he was happy with it. Although before publication the work was usually called Paul Morel, Lawrence finally settled on Sons and Lovers. Just as this changed title makes the work less focused on a central character, many of the latter additions broadened the scope of the work thereby making the work less autobiographical. While some of the edits by Garnett were on the grounds of propriety or style, others would once more narrow the emphasis back upon Paul.

In 1999, the Modern Library ranked Sons and Lovers ninth on a list of the 100 best novels in English of the 20th century

53. Halldor K. Laxness, Iceland, (1902-1998), Independent People

Independent People (Icelandic: Sjálfstætt fólk) is an epic novel by Halldór Laxness, published 1934-35. Its subject is the struggle of poor Icelandicfarmers in late 1800s/early 1900s, only freed from debt bondage in the last generation, and surviving on an isolated croft in inhospitable countryside.

Laxness was considered the main proponents of Social Realism in Icelandic fiction in the 1930s.

The novel is an indictment of materialism, the human relationship costs of the 'independent spirit', and perhaps capitalism itself. It helped propel Laxness to win the Nobel Prize in literature in 1955.

54. Giacomo Leopardi, Italy, (1798-1837), Complete Poems

| This image has been resized. Click this bar to view the full image. The original image is sized 576x600. |

55. Doris Lessing, England, (b.1919), The Golden Notebook

The Golden Notebook is the kind of novel every publisher waits for impatiently - a major work by a major talent. It is surely on of the most important English novels of our time.

Here in this labyrinth of overwhelmingly real stories is the full, complex story of a modern woman, Anna - a woman who will be talked about as were Ibsen's and Shaw's "new women" when the first appeared.

Anna tries to live with the freedom of a man. She is a writer, author of one very successful novel, who now keeps four notebooks. In one with a black cover she reviews the African experience of her earlier years. In a red one she records her political life, her disillusionment with Communism. In a yellow one she writes a novel in which her heroine relives part of her own experience. And in a blue one she keeps a personal diary.This book received the 1976 French Prix Medicis for Foreigners

Finally, in love with an American writer, threatened with insanity, Anna tries to bring the threads of all four books together in a golden notebook. With these various thread of her story - her life - Anna weaves a shatteringly vivid tapestry of contemporary concerns. Never for a moment can you doubt the validity of her testament.

Documentary precision combines with deep narrative art to reveal the truth of being an intelligent woman. Her conclusions are likely to be debated for generations.

56. Astrid Lindgren, Sweden, (1907), Pippi Longstocking

Pippi Longstocking (Swedish Pippi Långstrump) is a fictional character in a series of children's books created by author Astrid Lindgren.

Pippi is a nine-year-old girl, who lives with a complete lack of adult supervision. She is very unconventional, assertive, rich and extraordinarily strong, being able to lift her horse one-handed without difficulty.

She frequently mocks and dupes the adults she does encounter, an attitude likely to appeal to young readers; however, Pippi usually reserves her worst behavior for the most pompous and condescending of adults.

The first four Pippi books were published in 1945-48, with an additional series of five books published 1969-71. Two final stories were printed in 1979 and 2000. The books have later been translated into a large number of languages.

With the publication of the first Pippi book, Lindgren rejected established conventions for children's books. Although well received by contemporary critics, the book was controversial among some social conservatives who desired children's books that, by their standards, would set a good example for children.

| This image has been resized. Click this bar to view the full image. The original image is sized 622x470. |

Pippi's full name is Pippilotta Delicatessa Windowshade Mackrelmint Efraim's Daughter Longstocking (in the Swedish original Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump). Her fiery red hair is worn in braids that are so tightly wound that they stick out sideways from her head.

Pippi lives alone with her monkey, Mr. Nilsson, and her horse, Old Man, in an old house named Villa Villekulla, located in a small Swedish village. Her friends and next-door neighbors, Tommy and Annika Settergren, accompany her on her adventures; though the children's mother disapproves of Pippi's sometimes coarse manners and lack of education, Mrs. Settergren knows that Pippi would never put Tommy and Annika in harm's way, and that Pippi values her friendship with the pair above nearly all else in her life.

Though lacking in much formal education, Pippi is very intelligent in a common-sense fashion, and has a well-honed sense of justice and fair play. She will show respect (though still in her own unique style) for adults who treat her and other children fairly. Her attitude towards the worst of adults (from a child's viewpoint) is often that of a vapid, foolish and babblemouthed child, and few of her targets realize just how sharp and crafty Pippi is until she's made fools of them. Pippi has an amazing talent for spinning lies and tall tales, though they are usually in the form of humorously strange stories rather than lying with malicious intent.

Pippi is the daughter of seafarer Efraim Longstocking, captain of the sailing ship Hoptoad, from whom Pippi inherited her common sense and incredible strength, being the only person known who can match Pippi in physical ability. Captain Longstocking originally bought Villa Villekulla to give his daughter a more stable home life than that on shipboard (though Pippi loves the seafaring life, and is indeed a better sailor and helmswoman than most of her father's crew). Pippi retired to the Villa after her father was believed lost at sea, determined that her father was still alive and would come to look for her there.

As it turned out, Captain Longstocking was washed ashore upon a South Sea island known as Kurrekurredutt Isle, where he was made the "fat white chief" by its native people. The Captain returned to Sweden to bring Pippi to his new home in the South Seas, but Pippi found herself attached to the Villa and her new friends Tommy and Annika, and decided to stay where she was, though she and the children sometimes took trips with her father aboard the Hoptoad, including a trip to Kurrekurredutt where she was confirmed as the "fat white chief"'s daughter, Princess Pippilotta.

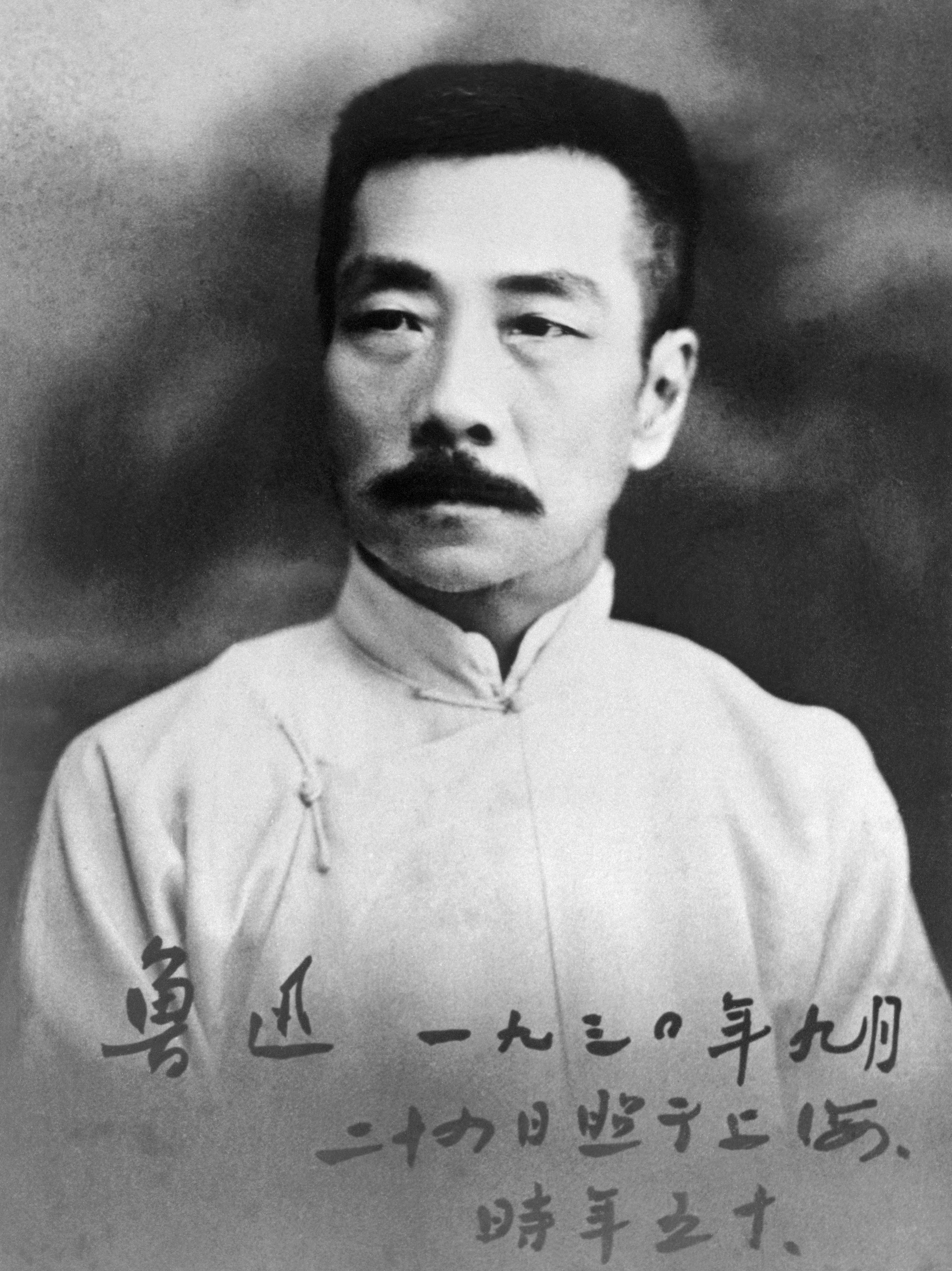

57. Lu Xun(Lỗ Tâ´n), China, (1881-1936), Diary of a Madman and Other Stories = AQ chính truyện

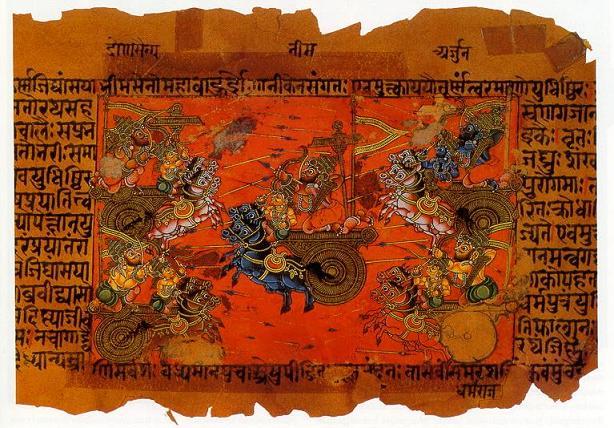

58. Mahabharata, India, (c. 500 BC)

| This image has been resized. Click this bar to view the full image. The original image is sized 614x428. |

59. Naguib Mahfouz, Egypt, (b. 1911), Children of Gebelawi

60. Thomas Mann, Germany, (1875-1955),

Buddenbrook;

61. Thomas Mann (Germany), The Magic Mountain

62. Herman Melville, United States, (1819-1891), Moby Dick

63. Michel de Montaigne, France, (1533-1592), Essays

64. Elsa Morante, Italy, (1918-1985), History

65.Toni Morrison, United States, (b. 1931), Beloved

(When slavery has torn apart one's heritage, when the past is more real than the present, when the rage of a dead baby can literally rock a house, then the traditional novel is no longer an adequate instrument. And so Pulitzer Prize-winner Beloved is written in bits and images, smashed like a mirror on the floor and left for the reader to put together. In a novel that is hypnotic, beautiful, and elusive, Toni Morrison portrays the lives of Sethe, an escaped slave and mother, and those around her. There is Sixo, who "stopped speaking English because there was no future in it," and .... Baby Suggs, who makes her living with her heart because slavery "had busted her legs, back, head, eyes, hands, kidneys, womb and tongue;" and Paul D, a man with a rusted metal box for a heart and a presence that allows women to cry. At the center is Sethe, whose story makes us think and think again about what we mean when we say we love our children or freedom. The stories circle, swim dreamily to the surface, and are suddenly clear and horrifying. Because of the extraordinary, experimental style as well as the intensity of the subject matter, what we learn from them touches at a level deeper than understanding.

(Review by Erica Bauermeister)

66. Shikibu Murasaki, Japan, (N/A), The Tale of Genji Genji

67. Robert Musil, Austria, (1880-1942), The Man Without Qualities (= Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften)

The Man without Qualities (German original title: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften) is a novel in three books by the Austrian novelist and essayistRobert Musil.

The main issue of the "story of ideas", which takes place in the time of Austria-Hungarian monarchy's last days, is the need of preserving the order in a shaken world (never considering the fact that World War I would start in a couple of months).

68. Vladimir Nabokov, Russia/United States, (1899-1977),Lolita

Lolita is a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, first published in 1955. The novel is both famous for its innovative style and infamous for its controversial subject: the book's narrator and main character Humbert Humbert becomes sexually obsessed with a pubescent girl, who is aged 12 years when most of the novel takes place.

The novel was adapted to film twice, once in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick (Nabokov was involved in the writing) and again in 1997 by Adrian Lyne.

69. Njaals Saga, Iceland, (c. 1300)

70. George Orwell, England, (1903-1950), 1984 Animal Farm

Animal Farm is a satiricalnovella (which can also be understood as a modernfable or allegory) by George Orwell, ostensibly about a group of animals who oust the humans from the farm on which they live.

They run the farm themselves, only to have it degenerate into a brutal tyrannyof its own. The book was written during World War II and published in 1945, although it was not widely successful until the late 1950s.

Animal Farm is a satiricalallegory of Soviettotalitarianism. Orwell based major events in the book on ones from the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, and a member of the Independent Labour Party for many years, was a critic of Stalin, and was suspicious of Moscow-directed Stalinismafter his experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

61. Thomas Mann (Germany), The Magic Mountain

62. Herman Melville, United States, (1819-1891), Moby Dick

63. Michel de Montaigne, France, (1533-1592), Essays

64. Elsa Morante, Italy, (1918-1985), History

65.Toni Morrison, United States, (b. 1931), Beloved

(When slavery has torn apart one's heritage, when the past is more real than the present, when the rage of a dead baby can literally rock a house, then the traditional novel is no longer an adequate instrument. And so Pulitzer Prize-winner Beloved is written in bits and images, smashed like a mirror on the floor and left for the reader to put together. In a novel that is hypnotic, beautiful, and elusive, Toni Morrison portrays the lives of Sethe, an escaped slave and mother, and those around her. There is Sixo, who "stopped speaking English because there was no future in it," and .... Baby Suggs, who makes her living with her heart because slavery "had busted her legs, back, head, eyes, hands, kidneys, womb and tongue;" and Paul D, a man with a rusted metal box for a heart and a presence that allows women to cry. At the center is Sethe, whose story makes us think and think again about what we mean when we say we love our children or freedom. The stories circle, swim dreamily to the surface, and are suddenly clear and horrifying. Because of the extraordinary, experimental style as well as the intensity of the subject matter, what we learn from them touches at a level deeper than understanding.

66. Shikibu Murasaki, Japan, (N/A), The Tale of Genji Genji

67. Robert Musil, Austria, (1880-1942), The Man Without Qualities (= Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften)

The Man without Qualities (German original title: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften) is a novel in three books by the Austrian novelist and essayistRobert Musil.

The main issue of the "story of ideas", which takes place in the time of Austria-Hungarian monarchy's last days, is the need of preserving the order in a shaken world (never considering the fact that World War I would start in a couple of months).

68. Vladimir Nabokov, Russia/United States, (1899-1977),Lolita

Lolita is a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, first published in 1955. The novel is both famous for its innovative style and infamous for its controversial subject: the book's narrator and main character Humbert Humbert becomes sexually obsessed with a pubescent girl, who is aged 12 years when most of the novel takes place.

The novel was adapted to film twice, once in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick (Nabokov was involved in the writing) and again in 1997 by Adrian Lyne.

69. Njaals Saga, Iceland, (c. 1300)

70. George Orwell, England, (1903-1950), 1984 Animal Farm

Animal Farm is a satiricalnovella (which can also be understood as a modernfable or allegory) by George Orwell, ostensibly about a group of animals who oust the humans from the farm on which they live.

They run the farm themselves, only to have it degenerate into a brutal tyrannyof its own. The book was written during World War II and published in 1945, although it was not widely successful until the late 1950s.

Animal Farm is a satiricalallegory of Soviettotalitarianism. Orwell based major events in the book on ones from the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, and a member of the Independent Labour Party for many years, was a critic of Stalin, and was suspicious of Moscow-directed Stalinismafter his experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

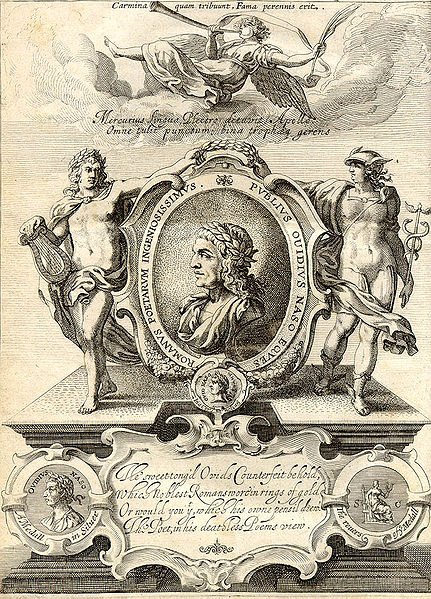

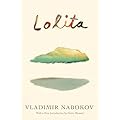

71. Ovid, Italy, (43 BC-17 e.Kr.), Metamorfoses

The Metamorphoses by the RomanpoetOvid is a poem in fifteen books that describes the creation and history of the world in terms according Greek andRoman points of view. It has remained one of the most popular works ofmythology, being the work best known to medieval writers and thus having a great deal of influence on medieval poetry.

72. Fernando Pessoa, Portugal, (1888-1935), The Book of Disquiet

The idea of the self is at the forefront of all of Pessoa's work, particularly The Book of Disquiet, his major prose piece. Tucked away in a trunk for more than fifty years after Pessoa's death, it was finally discovered (with thousands of other documents) and published in 1982.

Three English translations followed in 1991, of which Margaret Jull Costa's has been lauded as the finest. The book takes the form of a diary, written in extended fragments. Its author is Bernardo Soares, an assistant bookkeeper. Pessoa called Soares a "semi-heteronym" because his personality isn't so radically different from Pessoa's own.

Together they speak of Lisbon, literature (yes, even Soares writes of Caeiro and the others), monotony, dreams, commercialism, and much more, but in the final analysis, the minutiae of life is made heartbreakingly beautiful.

73. Edgar Allan Poe, United States, (1809-1849), The Complete Tales

Edgar Allan Poe 1848

74. Marcel Proust, France, (1871-1922), Remembrance of Things Past

In Search of Lost Time (fr. À la recherche du temps perdu) by Marcel Proustis a novel written in the form of an autobiography in seven volumes. Proust's most prominent work, it is popularly known for its length and the notion ofinvoluntary memory, the most famous example being the "episode of themadeleine."

Its title was known in English as Remembrance of Things Past until the early 1990s.

Published in France between 1913 and 1927, many of the novel's ideas, motifs, and scenes appear in adumbrated form in Proust's unfinished novel, Jean Santeuil (1896–99), and in his unfinished hybrid of philosophical essay and story, Contre Sainte-Beuve (1908–09).

At the risk of over-simplification, In Search of Lost Time can be viewed as abildungsroman in which the neurasthenic narrator discovers that he is a writer after a life spent distracted by society and love.

75. Francois Rabelais, France, (1495-1553), Gargantua and Pantagruel

Gargantua and Pantagruel is a connected series of five books written in the16th century by François Rabelais. It is the story of two giants, a father (Gargantua) and his son (Pantagruel) and their adventures, written in an amusing, extravagant, satirical vein. There is much crudity and scatological humor as well as needless violence. Long lists of vulgar insults fill several chapters.

Rabelais was one of the first Frenchmen to learn ancient Greek, from which he brought some 500 words into the French language. His quibbling and other wordplay fills the book, and is quite free from any prudishness.

The introduction to the cookie series runs (in an English translation):

Good friends, my Readers, who peruse this Book, Be not offended, whilst on it you look: Denude yourselves of all depraved affection, For it contains no badness, nor infection: 'Tis true that it brings forth to you no birth Of any value, but in point of mirth; Thinking therefore how sorrow might your mind Consume, I could no apter subject find; One inch of joy surmounts of grief a span; Because to laugh is proper to the man.

76. Juan Rulfo, Mexico, (1918-1986), Pedro Paramo

77. Jalal ad-din Rumi, Iran, (1207-1273), Mathnawi

78. Salman Rushdie, India/Britain, (b. 1947), Midnight's Children

Midnight's Children cover

Midnight's Children (ISBN 0-394-51470-X) is a 1980 novel by Salman Rushdie. It centres on the author's native India and was acclaimed as a major milestone in Post-colonial Literature.

Midnight's Children is a loose allegory for events in India both before and, primarily, after the independence and partition of India, which took place at midnight on 15 August1947. The protagonist and narrator of the story is Saleem Sinai, a telepath with a nasal defect, who is born at the exact moment that India becomes independent.

Saleem Sinai's life then parallels the changing fortunes of the country after independence.

The novel is also an expression of the author's own childhood, his affection for the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) in those times, and the tumultuous variety of the Indian subcontinent. The technique of magical realism finds liberal expression throughout the novel and is crucial to constructing the parallel to the country's history.

It has, therefore, been compared to One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. The novel is also recognised for its remarkably flexible and innovative use of the English language, with a liberal mix of native Indian languages, this being a departure from conventional Indian English writing.

The novel ran into some controversy for its open criticism of Indira Gandhi, India's then prime minister, and the Emergency that she imposed on the country.

The novel won the 1981 Booker Prize and was later awarded the 'Booker of Bookers' Prize in 1993 as the best novel to be awarded the Booker Prize in its first 25 years. Midnight's Children is also the only Indian novel on Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels since its founding in 1923

79. Sheikh Musharrif ud-din Sadi, Iran, (c. 1200-1292), The Orchard

80. Tayeb Salih, Sudan, (b. 1929), Season of Migration to the North

Considered a classic of the African Arabian (and, in its English translation, even Europhone) canon, this complex work manages to be at once subtle and shocking. It was first published (in Beirut, rather than in the author’s native Sudan) in 1967, in Arabic, and two years later in the English translation. The novel has a rather shadowy narrator figure, who could (some critics argue) be considered the actual central figure of the text, but he is greatly overshadowed by the man who (in the style of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner) imposes his own, strange story on the narrator and makes of him a sort of heir — this flamboyant character is called Mustafa Sa’eed (hereafter MS).

Both the narrator and the abovementioned MS are Sudanese who go to Britain for advanced study; MS in economics and the narrator in English literature. They meet in the small village along the Nile which is the narrator’s ‘home town’, where his beloved and ancient grandfather still lives. The villagers “were surprised when I told them that Europeans were, with minor differences, exactly like them” (3), the narrator tells us.

At this stage MS is to all intents and purposes an ordinary farmer, with a ‘local’ wife and two young sons. When MS (inadvertently, or deliberately?) quotes an English poem on a drunken evening, the narrator becomes suspicious. Most of the rest of the novel concerns his recollections of the exceedingly strange story that MS tells him — a story which haunts and oppresses, yet also challenges him in terms of defining his own value system in ‘postcolonial’ Sudanese society — in the context of “the new rulers of Africa, smooth of face, lupine of mouth, ... in suits of fine mohair and expensive silk” (118).

The narrator works as a bureaucrat in the Education ministry in Khartoum, but regularly visits his grandfather’s village, where he finds himself slowly falling in love with the widow of MS (who has in the meantime apparently been drowned in the flooded Nile).

The life story MS had narrated began with the account of his (British, colonial) schooling, which had led him to the discovery of his own mind, “like a sharp knife, cutting with cold effectiveness” (22). So brilliant is he that from Khartoum he is sent to Cairo and then to London for advanced study — here he is nicknamed “the black Englishman” (54).

In British society he becomes a sexual predator, setting up as his lair a room seductively decorated with ersatz ‘African’ paraphernalia. Englishwomen of a wide range of classes and ages easily succumb to and are destroyed by him. Three of these women are driven to suicide; while he eventually murders the most provocative of them, who had humiliated and taunted him before — and also during — their stormy marriage. This act (a sort of sex-murder) is in his own eyes, however, the grand consummation of his life:

‘The sensation that ... I have bedded the goddess of Death and gazed out upon Hell from the aperture of her eyes — it’s a feeling no man can imagine. The taste of that night stays on in my mouth, preventing me from savouring anything else.’ (153)

Elsewhere MS says of this relationship that he “was the invader who had come from the South, and this was the icy battlefield from which [he] would not make a safe return” (160). He kills Jean Morris (who invites this death) by pushing a knife into her chest between her breasts, and is jailed for seven years for the murder. This secret history persistently troubles MS’s confidant, the narrator.

Before MS (an excellent swimmer, we’re told) disappears — apparently drowned — he had written a letter to be given to the narrator (himself married, with a daughter), virtually ‘bequeathing’ him his two young sons. In the letter MS states that he is irresistibly drawn “towards faraway parts” (67). MS’s second, Sudanese wife (Hosna Bint Mahmoud) is, however, left prey to the sexual fancies of the much-married, 70-year-old Wad Rayes who (with the complicity of the village patriarchy) forces her into marriage while the narrator is away in Khartoum.

Hosna resists all her second husband’s advances. When he eventually attempts to rape her, she stabs him to death and then kills herself. Everyone in the village except the narrator is outraged that a woman (and a wife!) could have done this — shattering his idealised image of village society. Yet he is equally outraged at MS and construes Hosna as his (MS’s) final victim.

On his return to the village, the narrator at last enters a secret room that MS had built next to his home — a replica of a British gentleman’s drawing room! Pride of place has been given to MS’s painting of his ‘white’ wife, Jean Morris. The room also contains a book, purportedly the “Life Story” of MS, dedicated “To those who see with one eye ... and see things as ... either Eastern or Western” (150-151).

The book is completely blank. Filled with rage at everything that has happened, and also at himself, the narrator plunges into the Nile. A “numbness” strikes him, “half-way between north and south”, leaving him “unable to return” (167). From the water, he sees birds flying “northwards”, perhaps in a “migration”, and he “wak[es] from the nightmare” (168).

He decides that there are things worth living for, and he shouts for help (169). This brief account cannot accommodate the complicated structure, subtle allusiveness and richly metaphoric style of this difficult text, but may give some indication of its ironic (or sardonic) perspective and of its deep and lasting relevance to the political and cultural predicament of many Africans. Its demonstration of the harsh parallels between colonial racism and local sexism confirms that this text is, as Salih himself has stated, “a plea for toleration” at all levels. It is an unforgettable work.

81. Jose Saramago, Portugal, (b. 1922), Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological orpsychological factors.

Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define "blindness".

Total blindness is the complete lack of form and light perception and is clinically recorded as "NLP", an abbreviation for "no light perception".

"Blindness" is frequently used to describe severe visual impairment with residual vision. In order to determine which people may need special assistance because of their visual disabilities, various governmental jurisdictions have formulated more complex definitions referred to as legal blindness.

In North America and most of Europe, legal blindness is defined as visual acuity(vision) of 20/200 (6/60) or less in the better eye with best correction possible. This means that a legally blind individual would have to stand 20 feet from an object to see it with the same degree of clarity as a normally sighted person could from 200 feet. In many areas, people with average acuity who nonetheless have a visual field of less than 20 degrees (the norm being 60 degrees) are also classified as being legally blind. Approximately ten percent of those deemed legally blind, by any measure, are fully sightless. The rest have some vision, from light perception alone to relatively good acuity. Those who are not legally blind, but nonetheless have serious visual impairments, possesslow vision.

82. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616), Hamlet;

83. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616 King Lear;

84. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616 Othello

Shakespeare

85. Sophocles, Greece, (496-406 BC), Oedipus the King

Oedipus the King (Greek Oἰδίπoυς τύραννoς, "Oedipus Tyrannos"), also known as Oedipus Rex, is a Greektragedy, written by Sophocles and first performed in428 BC. The play was the second of Sophocles' three Theban plays to be produced, but comes first in the internal chronology of the plays, followed byOedipus at Colonus and then Antigone

86. Stendhal, France, (1783-1842), The Red and the Black

Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black) is a novel by Stendhal, published in 1830. The title has been translated into English variously as Scarlet and Black, Red and Black, and The Red and the Black. It is set in France circa1827-30, and relates a young man's attempts to rise above his plebeian birth through a combination of talent, hard work, deception and hypocrisy, only to find himself betrayed by his own passions.

As in Stendhal's later novel The Charterhouse of Parma (La Chartreuse de Parme), the protagonist, Julien Sorel, is a driven and intelligent man, but equally fails to understand much about the ways of the world he sets out to conquer. He harbours many romantic illusions, and becomes little more than a pawn in the political machinations of the influential and ruthless people who surround him. Stendhal uses his flawed hero to satirize French society of the time, particularly the hypocrisy and materialism of its aristocracy and theRoman Catholic Church, and to foretell a radical change in French society that will remove both of those forces from their positions of power.

The most common and most likely explanation of the title is that red and black are the contrasting colors of the army uniform of the times and of the robes of priests, respectively. Alternative explanations are possible, however: for example, red might stand for love and black for death and mourning; or the colours might refer to those of a roulette wheel, and may indicate the unexpected changes in the hero's career.

87. Laurence Sterne, Ireland, (1713-1768), The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (or, more briefly,Tristram Shandy) is a novel by Laurence Sterne. It was published in nine volumes, the first two appearing in 1759, and seven others following over the next 10 years. It was not always held in high esteem by other writers (Samuel Johnson responded that, "Nothing odd will do long" ), but its bawdy humour was popular with London society, and it has come to be seen as one of the greatest comic novels in English, as well as a forerunner for many modern narrative devices.

As its title suggests, the book is ostensibly Tristram's narration of his life story. But it is one of the central jokes of the novel that he cannot explain anything simply without making explanatory diversions to add context and colour to his tale, to the extent that we do not even reach Tristram's own birth until Volume III.

Consequently, apart from Tristram as narrator, the most familiar and important characters in the book are his father Walter, his mother, his Uncle Toby, Toby's servant Trim, and a supporting cast of popular minor characters including Doctor Slop and the parson Yorrick.

Most of the action is concerned with domestic upsets or misunderstandings, which find humour in the opposing temperaments of Walter – splenetic, rational and somewhat sarcastic – and Uncle Toby, who is gentle, uncomplicated and a lover of his fellow man.

In between such events, Tristram as narrator finds himself discoursing at length on sexual practices, insults, the influence of one's name, noses, as well as explorations of obstetrics, siege warfare and philosophy, as he struggles to marshall his material and finish the story of his life.

88. Italo Svevo, Italy, (1861-1928), Confessions of Zeno = La coscienza di Zeno

The novel is presented as a diary written by Zeno (who claims that it is full of lies), published by his doctor. The doctor has left a little note in the beginning, saying that he had Zeno write his autobiography in order to help him in hispsychoanalysis. The doctor has published the work as revenge for Zeno discontinuing his visits.

Zeno first writes about his cigarette addiction and cites the first times that he smoked. In his first few paragraphs, he remembers his life as a child.

One of his friends would buy for him and his brother cigarettes, which they would smoke. Soon, he steals money from his father in order to buy tobacco, and he finally decides not to do this out of shame. Eventually, he starts to smoke his father's half-smoked cigars instead. The problem with his "last cigarette" starts when he is twenty.

He contracts a fever and his doctor tells him that he must abstain from smoking in order for him to heal. He decides that smoking is bad for him and he smokes his "last cigarette" so he can quit. However, this is not his last and he soon becomes plagued with "last cigarettes." He attempts to quit on days of important events in his life and soon obsessively attempts to quit on the basis of the harmony in the numbers of dates.

Each time, he fails to let his last cigarette be truly the last. He goes to doctors and asks friends for help in order to give up the habit, but to no avail each time. He goes so far as to break out of a clinic that he commits himself into.

When Zeno hits middle age, his father's health begins to deteriorate. He starts to live closer to his father in case he passes away. Zeno is very different from his father, who is a serious man, while Zeno likes to joke.

For instance, when his father states that Zeno is crazy, Zeno goes to the doctor and gets an official certification that he is sane. He shows this to his father who is hurt by this joke and becomes even more convinced that Zeno must be crazy. His father is also afraid of death, being very uncomfortable with the drafting of his will. One night, his father falls gravely ill and loses consciousness. The doctor comes and works on the patient, who is brought out of the clutches of death momentarily.

Over the next few days, his father is able to get up and regains a bit of his self. He is restless and shifts positions for comfort often, even though the doctor says that staying in bed would be good for his circulation. One night, as his father tries to roll out of bed, Zeno blocks him from moving, to do as the doctor wished. His angry father then stands up and slaps Zeno in the face before dying.

His memoirs then trace how he meets his wife. When he is starting to learn about the business world, he meets his future father-in-law Giovanni Malfenti, an intelligent and successful businessman, whom Zeno admires.

Malfenti has four daughters, Ada, Augusta, Alberta, and Anna, and when Zeno meets them, he decides that he wants to court Ada because of her beauty and since Alberta is quite young, while he regards Augusta as too plain, and Anna is only a little girl. He is unsuccessful and the Malfentis think that he is actually trying to court Augusta.

He soon meets his rival for Ada's love, who is Guido Speier. Guido speaks perfectTuscan (while Zeno speaks the dialect of Trieste), is handsome, and has a full head of hair (compared with Zeno's bald head). That evening, while Guido and Zeno both visit the Malfentis, Zeno proposes to Ada and she rejects him for Guido. Zeno then proposes to Alberta, who is not interested in marrying, and he is rejected by her also. Finally, he proposes to Augusta (who knows that Zeno first proposed to the other two) and she accepts, because she loves him.

Very soon, the couples get married and Zeno starts to realize that he can love Augusta. This surprises him as his love for her does not diminish.

However, he meets a poor aspiring singer by the name of Carla and they start an affair, with Carla thinking that Zeno does not love his wife. Meanwhile, Ada and Guido marry and Signior Malfenti gets sick. Zeno's affection for both Augusta and Carla increases and he has a daughter by the name of Antonia around the time Giovanni passes away. Finally, one day, Carla expresses a sudden whim to see Augusta. Zeno deceives Carla and causes her to meet Ada instead. Carla misrepresents Ada as Zeno's wife, and moved by her beauty, breaks off the affair.

Zeno goes on to relate the business partnership between him and Guido. The two men set up a merchant business together in Trieste. They hire two workers named Luciano and Carmen (who becomes Guido's mistress) and they attempt to make as much profit as possible.

However, due to Guido's obsession with debts and credit as well as with the notion of profit, the company does poorly. Guido and Ada's marriage begin to crumble and so does Ada's health and beauty. Guido fakes a suicide attempt in order to gain Ada's compassion and she asks Zeno to help Guido's failing company.

Guido starts playing on the Bourse (stock exchange) and loses even more money. On a fishing trip, he asks Zeno about the differences in effects between sodium veronal and veronal and Zeno answers that sodium veronal is fatal while veronal is not. Guido's gambling on the Bourse becomes very destructive and he finally tries to fake another suicide in order to gain Ada's compassion. However, he takes a fatal amount of veronal and dies. Soon thereafter, Zeno misses Guido's funeral because he himself gambles Guido's money on the Bourse and recovers three quarters of the losses.

Zeno relates his current life. It is during the time of the Great War and his daughter Antonia (who greatly resembles Ada) and son Alfio have grown up.

His time is spent on visiting doctors to cure his supposed imagined sickness. One of the doctors claims that he is suffering from the Oedipus complex, but Zeno does not believe it to be true. All the doctors are not able to treat him. Finally, he realizes that life itself resembles sickness because it has advancements and setbacks and always ends in death. Human advancement prolongs life and it is that which causes more sickness and weakness in humans. Zeno imagines a time when a person will invent a new, powerful weapon of mass destruction and another will steal it and destroy the world, setting it free of sickness.

89. Jonathan Swift, Ireland, (1667-1745), Gulliver's Travels

First Edition of Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels (1726, amended 1735), officially Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, is a novel by Jonathan Swift that is both asatire on human nature and a parody of the "travellers' tales" literary sub-genre. It is widely considered Swift's magnum opus and is his most celebrated work, as well as one of the indisputable classics of English literature.

The book became tremendously popular as soon as it was published (Alexander Pope stated that "it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery"), and it is likely that it has never been out of print since then.

George Orwell declared it to be among the six indispensable books in world literature. It is claimed the inspiration for Gulliver came from the sleeping giant profile of the Cavehill in Belfast.

The book presents itself as a simple traveller's narrative with the disingenuous title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, its authorship assigned only to "Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, then a captain of several ships". Different editions contain different versions of the prefatory material which are basically the same as forewords in modern books.

The book proper then is divided into four parts, which are as follows.

Part I: A Voyage To Lilliput

The book begins with a short preamble in which Gulliver, in the style of books of the time, gives a brief outline of his life and history prior to his voyages. We learn he is middle-aged and middle-class, with a talent for medicine and languages, and that he enjoys travelling. This turns out to be fortunate. Upon careful reading, this introduction proves to be one of the most satirical points in the book: laced with innuendos and other forms of ironic humour: a trademark of Swift's writing.

On his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and awakes to find himself a prisoner of a race of 6 inch (15cm) tall people, inhabitants of the neighbouring and rival countries ofLilliput and Blefuscu. After giving assurances of his good behaviour he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the court.

There follow Gulliver's observations on the Court of Lilliput, which is intended to satirise the court of then King George I. After he assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudans (by stealing their fleet) but refuses to reduce the country to a province of Lilliput, he is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded.

Fortunately, Gulliver escapes to Blefuscu, where he builds a raft and sails out to a ship that he spotted on the horizon which takes him back home. The feuding between the Lilliputians and the Blefuscudans is meant to represent the feuding countries of England and France, but the reason for the war is meant to satirize the feud between Catholics and Protestants.

Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag

Gulliver Exhibited to the Brobdingnag Farmer

While exploring a new country, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and found by a farmer who is 72 feet (22 meters) tall (the scale of Lilliput is approximately 12:1, of Brobdingnag 1:12) who treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. He is then bought by the Queen of Brobdingnag and kept as a favourite at court.

In between small adventures such as fighting giant flies and being carried to the roof by a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the King, who is not impressed.

On a trip to the seaside, his "travelling box" is seized by a giant eagle and dropped into the sea where he is picked up by sailors and returned to England.

Part III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Glubbdubdrib, Luggnagg and Japan

Part IV: A Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms

(còn tiê´p)

90 . Leo Tolstoy, Russia, (1828-1910), War and Peace = Война и мир, Voyna i mir; Chiê´n tranh và hòa bình ;

War and Peace depicts a huge cast of characters, both historical and fictional, the majority of whom are introduced in the first book. At a soirée given by Anna Pavlovna Scherer in July 1805, the main players and families of the novel are made known. Pierre Bezukhovis the illegitimate son of a wealthycountwho is dying of a stroke, and becomes unexpectedly embroiled in a tussle for his inheritance.

The intelligent and sardonic Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, husband of a charming wife Lise, finds little comfort in married life, instead choosing to be aide-de-camp of Prince Mikhail Kutuzov in their coming war againstNapoleon. We learn too of the Moscow Rostov family, with four adolescent children, of whom the vivacious younger daughter Natalya Rostova ("Natasha") and impetuous older Nikolai Rostov are the most memorable. At Bald Hills, Prince Andrei leaves his pregnant wife to his eccentric father and religiously devout sister Maria Bolkonskaya and leaves for war.

If there is a central character to War and Peace it is Pierre Bezukhov who, upon receiving an unexpected inheritance, is suddenly burdened with the responsibilities and conflicts of a Russian nobleman. His former carefree behavior vanishes and he enters upon a philosophical quest particular to Tolstoy: how should one live a moral life in an imperfect world? He attempts to free his peasants and improve his estate, but ultimately achieves nothing. He enters into marriage with Prince Kuragin's beautiful and immoral daughter Elena, against his own better judgement.

Elena and her brother Anatoly then conspire together for Anatoly to seduce and dishonor the young and beautiful Natasha Rostova. This plan fails, yet, for Pierre, it is the cause of an important meeting with Natasha. When Napoleoninvades Russia, Pierre observes the Battle of Borodino up close by standing near a Russian artillery crew and he learns how bloody and horrific war really is. When Napoleon's Grand Army occupies an abandoned and burning Moscow, Pierre takes off on a quixotic mission to assassinate Napoleon and is captured as a prisoner of war. After witnessing French soldiers sacking Moscow and shooting Russian civilians, Pierre is forced to march with the Grand Army during its disastrous retreat from Moscow.

He is later freed by a Russian raiding party. His wife Elena dies sometime during the last throes of Napoleon's invasion and Pierre is reunited with Natasha while the victorious Russians rebuild Moscow. Pierre finds love at last and marries Natasha, while Nikolai marries Maria Bolkonskaya.

Andrei, who was also in love with Natasha, is wounded during Napoleon's invasion and eventually dies after being reunited with Natasha before the end of the war.

A scene from Sergei Bondarchuk's production of War and Peace

Tolstoy vividly depicts the contrast between Napoleon and the Russian generalKutuzov, both in terms of personality and in the clash of armies. Napoleon chose wrongly, opting to march on to Moscow and occupy it for five fatal weeks, when he would have been better off destroying the Russian army in a decisive battle.

General Kutuzov believes time to be his best ally, and refrains from engaging the French, who ultimately destroy themselves as they limp back toward the French border. They are all but destroyed by a final Cossack attack as they straggle back toward Paris.

62. Herman Melville, United States, (1819-1891), Moby Dick

63. Michel de Montaigne, France, (1533-1592), Essays

64. Elsa Morante, Italy, (1918-1985), History

65.Toni Morrison, United States, (b. 1931), Beloved

(When slavery has torn apart one's heritage, when the past is more real than the present, when the rage of a dead baby can literally rock a house, then the traditional novel is no longer an adequate instrument. And so Pulitzer Prize-winner Beloved is written in bits and images, smashed like a mirror on the floor and left for the reader to put together. In a novel that is hypnotic, beautiful, and elusive, Toni Morrison portrays the lives of Sethe, an escaped slave and mother, and those around her. There is Sixo, who "stopped speaking English because there was no future in it," and .... Baby Suggs, who makes her living with her heart because slavery "had busted her legs, back, head, eyes, hands, kidneys, womb and tongue;" and Paul D, a man with a rusted metal box for a heart and a presence that allows women to cry. At the center is Sethe, whose story makes us think and think again about what we mean when we say we love our children or freedom. The stories circle, swim dreamily to the surface, and are suddenly clear and horrifying. Because of the extraordinary, experimental style as well as the intensity of the subject matter, what we learn from them touches at a level deeper than understanding.

(Review by Erica Bauermeister)

66. Shikibu Murasaki, Japan, (N/A), The Tale of Genji Genji

67. Robert Musil, Austria, (1880-1942), The Man Without Qualities (= Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften)

The Man without Qualities (German original title: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften) is a novel in three books by the Austrian novelist and essayistRobert Musil.

The main issue of the "story of ideas", which takes place in the time of Austria-Hungarian monarchy's last days, is the need of preserving the order in a shaken world (never considering the fact that World War I would start in a couple of months).

68. Vladimir Nabokov, Russia/United States, (1899-1977),Lolita

Lolita is a novel by Vladimir Nabokov, first published in 1955. The novel is both famous for its innovative style and infamous for its controversial subject: the book's narrator and main character Humbert Humbert becomes sexually obsessed with a pubescent girl, who is aged 12 years when most of the novel takes place.

The novel was adapted to film twice, once in 1962 by Stanley Kubrick (Nabokov was involved in the writing) and again in 1997 by Adrian Lyne.

69. Njaals Saga, Iceland, (c. 1300)

70. George Orwell, England, (1903-1950), 1984 Animal Farm

Animal Farm is a satiricalnovella (which can also be understood as a modernfable or allegory) by George Orwell, ostensibly about a group of animals who oust the humans from the farm on which they live.

They run the farm themselves, only to have it degenerate into a brutal tyrannyof its own. The book was written during World War II and published in 1945, although it was not widely successful until the late 1950s.

Animal Farm is a satiricalallegory of Soviettotalitarianism. Orwell based major events in the book on ones from the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, and a member of the Independent Labour Party for many years, was a critic of Stalin, and was suspicious of Moscow-directed Stalinismafter his experiences in the Spanish Civil War.

71. Ovid, Italy, (43 BC-17 e.Kr.), Metamorfoses

The Metamorphoses by the RomanpoetOvid is a poem in fifteen books that describes the creation and history of the world in terms according Greek andRoman points of view. It has remained one of the most popular works ofmythology, being the work best known to medieval writers and thus having a great deal of influence on medieval poetry.

72. Fernando Pessoa, Portugal, (1888-1935), The Book of Disquiet

The idea of the self is at the forefront of all of Pessoa's work, particularly The Book of Disquiet, his major prose piece. Tucked away in a trunk for more than fifty years after Pessoa's death, it was finally discovered (with thousands of other documents) and published in 1982.

Three English translations followed in 1991, of which Margaret Jull Costa's has been lauded as the finest. The book takes the form of a diary, written in extended fragments. Its author is Bernardo Soares, an assistant bookkeeper. Pessoa called Soares a "semi-heteronym" because his personality isn't so radically different from Pessoa's own.

Together they speak of Lisbon, literature (yes, even Soares writes of Caeiro and the others), monotony, dreams, commercialism, and much more, but in the final analysis, the minutiae of life is made heartbreakingly beautiful.

73. Edgar Allan Poe, United States, (1809-1849), The Complete Tales

Edgar Allan Poe 1848

74. Marcel Proust, France, (1871-1922), Remembrance of Things Past

In Search of Lost Time (fr. À la recherche du temps perdu) by Marcel Proustis a novel written in the form of an autobiography in seven volumes. Proust's most prominent work, it is popularly known for its length and the notion ofinvoluntary memory, the most famous example being the "episode of themadeleine."

Its title was known in English as Remembrance of Things Past until the early 1990s.

Published in France between 1913 and 1927, many of the novel's ideas, motifs, and scenes appear in adumbrated form in Proust's unfinished novel, Jean Santeuil (1896–99), and in his unfinished hybrid of philosophical essay and story, Contre Sainte-Beuve (1908–09).

At the risk of over-simplification, In Search of Lost Time can be viewed as abildungsroman in which the neurasthenic narrator discovers that he is a writer after a life spent distracted by society and love.

75. Francois Rabelais, France, (1495-1553), Gargantua and Pantagruel

Gargantua and Pantagruel is a connected series of five books written in the16th century by François Rabelais. It is the story of two giants, a father (Gargantua) and his son (Pantagruel) and their adventures, written in an amusing, extravagant, satirical vein. There is much crudity and scatological humor as well as needless violence. Long lists of vulgar insults fill several chapters.

Rabelais was one of the first Frenchmen to learn ancient Greek, from which he brought some 500 words into the French language. His quibbling and other wordplay fills the book, and is quite free from any prudishness.

The introduction to the cookie series runs (in an English translation):

Good friends, my Readers, who peruse this Book, Be not offended, whilst on it you look: Denude yourselves of all depraved affection, For it contains no badness, nor infection: 'Tis true that it brings forth to you no birth Of any value, but in point of mirth; Thinking therefore how sorrow might your mind Consume, I could no apter subject find; One inch of joy surmounts of grief a span; Because to laugh is proper to the man.

76. Juan Rulfo, Mexico, (1918-1986), Pedro Paramo

77. Jalal ad-din Rumi, Iran, (1207-1273), Mathnawi

78. Salman Rushdie, India/Britain, (b. 1947), Midnight's Children

Midnight's Children cover

Midnight's Children (ISBN 0-394-51470-X) is a 1980 novel by Salman Rushdie. It centres on the author's native India and was acclaimed as a major milestone in Post-colonial Literature.

Midnight's Children is a loose allegory for events in India both before and, primarily, after the independence and partition of India, which took place at midnight on 15 August1947. The protagonist and narrator of the story is Saleem Sinai, a telepath with a nasal defect, who is born at the exact moment that India becomes independent.

Saleem Sinai's life then parallels the changing fortunes of the country after independence.

The novel is also an expression of the author's own childhood, his affection for the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) in those times, and the tumultuous variety of the Indian subcontinent. The technique of magical realism finds liberal expression throughout the novel and is crucial to constructing the parallel to the country's history.

It has, therefore, been compared to One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. The novel is also recognised for its remarkably flexible and innovative use of the English language, with a liberal mix of native Indian languages, this being a departure from conventional Indian English writing.

The novel ran into some controversy for its open criticism of Indira Gandhi, India's then prime minister, and the Emergency that she imposed on the country.

The novel won the 1981 Booker Prize and was later awarded the 'Booker of Bookers' Prize in 1993 as the best novel to be awarded the Booker Prize in its first 25 years. Midnight's Children is also the only Indian novel on Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels since its founding in 1923

79. Sheikh Musharrif ud-din Sadi, Iran, (c. 1200-1292), The Orchard

80. Tayeb Salih, Sudan, (b. 1929), Season of Migration to the North

Considered a classic of the African Arabian (and, in its English translation, even Europhone) canon, this complex work manages to be at once subtle and shocking. It was first published (in Beirut, rather than in the author’s native Sudan) in 1967, in Arabic, and two years later in the English translation. The novel has a rather shadowy narrator figure, who could (some critics argue) be considered the actual central figure of the text, but he is greatly overshadowed by the man who (in the style of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner) imposes his own, strange story on the narrator and makes of him a sort of heir — this flamboyant character is called Mustafa Sa’eed (hereafter MS).

Both the narrator and the abovementioned MS are Sudanese who go to Britain for advanced study; MS in economics and the narrator in English literature. They meet in the small village along the Nile which is the narrator’s ‘home town’, where his beloved and ancient grandfather still lives. The villagers “were surprised when I told them that Europeans were, with minor differences, exactly like them” (3), the narrator tells us.

At this stage MS is to all intents and purposes an ordinary farmer, with a ‘local’ wife and two young sons. When MS (inadvertently, or deliberately?) quotes an English poem on a drunken evening, the narrator becomes suspicious. Most of the rest of the novel concerns his recollections of the exceedingly strange story that MS tells him — a story which haunts and oppresses, yet also challenges him in terms of defining his own value system in ‘postcolonial’ Sudanese society — in the context of “the new rulers of Africa, smooth of face, lupine of mouth, ... in suits of fine mohair and expensive silk” (118).

The narrator works as a bureaucrat in the Education ministry in Khartoum, but regularly visits his grandfather’s village, where he finds himself slowly falling in love with the widow of MS (who has in the meantime apparently been drowned in the flooded Nile).

The life story MS had narrated began with the account of his (British, colonial) schooling, which had led him to the discovery of his own mind, “like a sharp knife, cutting with cold effectiveness” (22). So brilliant is he that from Khartoum he is sent to Cairo and then to London for advanced study — here he is nicknamed “the black Englishman” (54).

In British society he becomes a sexual predator, setting up as his lair a room seductively decorated with ersatz ‘African’ paraphernalia. Englishwomen of a wide range of classes and ages easily succumb to and are destroyed by him. Three of these women are driven to suicide; while he eventually murders the most provocative of them, who had humiliated and taunted him before — and also during — their stormy marriage. This act (a sort of sex-murder) is in his own eyes, however, the grand consummation of his life:

‘The sensation that ... I have bedded the goddess of Death and gazed out upon Hell from the aperture of her eyes — it’s a feeling no man can imagine. The taste of that night stays on in my mouth, preventing me from savouring anything else.’ (153)

Elsewhere MS says of this relationship that he “was the invader who had come from the South, and this was the icy battlefield from which [he] would not make a safe return” (160). He kills Jean Morris (who invites this death) by pushing a knife into her chest between her breasts, and is jailed for seven years for the murder. This secret history persistently troubles MS’s confidant, the narrator.

Before MS (an excellent swimmer, we’re told) disappears — apparently drowned — he had written a letter to be given to the narrator (himself married, with a daughter), virtually ‘bequeathing’ him his two young sons. In the letter MS states that he is irresistibly drawn “towards faraway parts” (67). MS’s second, Sudanese wife (Hosna Bint Mahmoud) is, however, left prey to the sexual fancies of the much-married, 70-year-old Wad Rayes who (with the complicity of the village patriarchy) forces her into marriage while the narrator is away in Khartoum.

Hosna resists all her second husband’s advances. When he eventually attempts to rape her, she stabs him to death and then kills herself. Everyone in the village except the narrator is outraged that a woman (and a wife!) could have done this — shattering his idealised image of village society. Yet he is equally outraged at MS and construes Hosna as his (MS’s) final victim.

On his return to the village, the narrator at last enters a secret room that MS had built next to his home — a replica of a British gentleman’s drawing room! Pride of place has been given to MS’s painting of his ‘white’ wife, Jean Morris. The room also contains a book, purportedly the “Life Story” of MS, dedicated “To those who see with one eye ... and see things as ... either Eastern or Western” (150-151).

The book is completely blank. Filled with rage at everything that has happened, and also at himself, the narrator plunges into the Nile. A “numbness” strikes him, “half-way between north and south”, leaving him “unable to return” (167). From the water, he sees birds flying “northwards”, perhaps in a “migration”, and he “wak[es] from the nightmare” (168).

He decides that there are things worth living for, and he shouts for help (169). This brief account cannot accommodate the complicated structure, subtle allusiveness and richly metaphoric style of this difficult text, but may give some indication of its ironic (or sardonic) perspective and of its deep and lasting relevance to the political and cultural predicament of many Africans. Its demonstration of the harsh parallels between colonial racism and local sexism confirms that this text is, as Salih himself has stated, “a plea for toleration” at all levels. It is an unforgettable work.

81. Jose Saramago, Portugal, (b. 1922), Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological orpsychological factors.

Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define "blindness".

Total blindness is the complete lack of form and light perception and is clinically recorded as "NLP", an abbreviation for "no light perception".

"Blindness" is frequently used to describe severe visual impairment with residual vision. In order to determine which people may need special assistance because of their visual disabilities, various governmental jurisdictions have formulated more complex definitions referred to as legal blindness.

In North America and most of Europe, legal blindness is defined as visual acuity(vision) of 20/200 (6/60) or less in the better eye with best correction possible. This means that a legally blind individual would have to stand 20 feet from an object to see it with the same degree of clarity as a normally sighted person could from 200 feet. In many areas, people with average acuity who nonetheless have a visual field of less than 20 degrees (the norm being 60 degrees) are also classified as being legally blind. Approximately ten percent of those deemed legally blind, by any measure, are fully sightless. The rest have some vision, from light perception alone to relatively good acuity. Those who are not legally blind, but nonetheless have serious visual impairments, possesslow vision.

82. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616), Hamlet;

83. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616 King Lear;

84. William Shakespeare, England, (1564-1616 Othello

Shakespeare

85. Sophocles, Greece, (496-406 BC), Oedipus the King

Oedipus the King (Greek Oἰδίπoυς τύραννoς, "Oedipus Tyrannos"), also known as Oedipus Rex, is a Greektragedy, written by Sophocles and first performed in428 BC. The play was the second of Sophocles' three Theban plays to be produced, but comes first in the internal chronology of the plays, followed byOedipus at Colonus and then Antigone

86. Stendhal, France, (1783-1842), The Red and the Black

Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black) is a novel by Stendhal, published in 1830. The title has been translated into English variously as Scarlet and Black, Red and Black, and The Red and the Black. It is set in France circa1827-30, and relates a young man's attempts to rise above his plebeian birth through a combination of talent, hard work, deception and hypocrisy, only to find himself betrayed by his own passions.

As in Stendhal's later novel The Charterhouse of Parma (La Chartreuse de Parme), the protagonist, Julien Sorel, is a driven and intelligent man, but equally fails to understand much about the ways of the world he sets out to conquer. He harbours many romantic illusions, and becomes little more than a pawn in the political machinations of the influential and ruthless people who surround him. Stendhal uses his flawed hero to satirize French society of the time, particularly the hypocrisy and materialism of its aristocracy and theRoman Catholic Church, and to foretell a radical change in French society that will remove both of those forces from their positions of power.

The most common and most likely explanation of the title is that red and black are the contrasting colors of the army uniform of the times and of the robes of priests, respectively. Alternative explanations are possible, however: for example, red might stand for love and black for death and mourning; or the colours might refer to those of a roulette wheel, and may indicate the unexpected changes in the hero's career.

87. Laurence Sterne, Ireland, (1713-1768), The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (or, more briefly,Tristram Shandy) is a novel by Laurence Sterne. It was published in nine volumes, the first two appearing in 1759, and seven others following over the next 10 years. It was not always held in high esteem by other writers (Samuel Johnson responded that, "Nothing odd will do long" ), but its bawdy humour was popular with London society, and it has come to be seen as one of the greatest comic novels in English, as well as a forerunner for many modern narrative devices.

As its title suggests, the book is ostensibly Tristram's narration of his life story. But it is one of the central jokes of the novel that he cannot explain anything simply without making explanatory diversions to add context and colour to his tale, to the extent that we do not even reach Tristram's own birth until Volume III.

Consequently, apart from Tristram as narrator, the most familiar and important characters in the book are his father Walter, his mother, his Uncle Toby, Toby's servant Trim, and a supporting cast of popular minor characters including Doctor Slop and the parson Yorrick.

Most of the action is concerned with domestic upsets or misunderstandings, which find humour in the opposing temperaments of Walter – splenetic, rational and somewhat sarcastic – and Uncle Toby, who is gentle, uncomplicated and a lover of his fellow man.

In between such events, Tristram as narrator finds himself discoursing at length on sexual practices, insults, the influence of one's name, noses, as well as explorations of obstetrics, siege warfare and philosophy, as he struggles to marshall his material and finish the story of his life.

88. Italo Svevo, Italy, (1861-1928), Confessions of Zeno = La coscienza di Zeno

The novel is presented as a diary written by Zeno (who claims that it is full of lies), published by his doctor. The doctor has left a little note in the beginning, saying that he had Zeno write his autobiography in order to help him in hispsychoanalysis. The doctor has published the work as revenge for Zeno discontinuing his visits.

Zeno first writes about his cigarette addiction and cites the first times that he smoked. In his first few paragraphs, he remembers his life as a child.

One of his friends would buy for him and his brother cigarettes, which they would smoke. Soon, he steals money from his father in order to buy tobacco, and he finally decides not to do this out of shame. Eventually, he starts to smoke his father's half-smoked cigars instead. The problem with his "last cigarette" starts when he is twenty.

He contracts a fever and his doctor tells him that he must abstain from smoking in order for him to heal. He decides that smoking is bad for him and he smokes his "last cigarette" so he can quit. However, this is not his last and he soon becomes plagued with "last cigarettes." He attempts to quit on days of important events in his life and soon obsessively attempts to quit on the basis of the harmony in the numbers of dates.

Each time, he fails to let his last cigarette be truly the last. He goes to doctors and asks friends for help in order to give up the habit, but to no avail each time. He goes so far as to break out of a clinic that he commits himself into.

When Zeno hits middle age, his father's health begins to deteriorate. He starts to live closer to his father in case he passes away. Zeno is very different from his father, who is a serious man, while Zeno likes to joke.

For instance, when his father states that Zeno is crazy, Zeno goes to the doctor and gets an official certification that he is sane. He shows this to his father who is hurt by this joke and becomes even more convinced that Zeno must be crazy. His father is also afraid of death, being very uncomfortable with the drafting of his will. One night, his father falls gravely ill and loses consciousness. The doctor comes and works on the patient, who is brought out of the clutches of death momentarily.

Over the next few days, his father is able to get up and regains a bit of his self. He is restless and shifts positions for comfort often, even though the doctor says that staying in bed would be good for his circulation. One night, as his father tries to roll out of bed, Zeno blocks him from moving, to do as the doctor wished. His angry father then stands up and slaps Zeno in the face before dying.

His memoirs then trace how he meets his wife. When he is starting to learn about the business world, he meets his future father-in-law Giovanni Malfenti, an intelligent and successful businessman, whom Zeno admires.

Malfenti has four daughters, Ada, Augusta, Alberta, and Anna, and when Zeno meets them, he decides that he wants to court Ada because of her beauty and since Alberta is quite young, while he regards Augusta as too plain, and Anna is only a little girl. He is unsuccessful and the Malfentis think that he is actually trying to court Augusta.

He soon meets his rival for Ada's love, who is Guido Speier. Guido speaks perfectTuscan (while Zeno speaks the dialect of Trieste), is handsome, and has a full head of hair (compared with Zeno's bald head). That evening, while Guido and Zeno both visit the Malfentis, Zeno proposes to Ada and she rejects him for Guido. Zeno then proposes to Alberta, who is not interested in marrying, and he is rejected by her also. Finally, he proposes to Augusta (who knows that Zeno first proposed to the other two) and she accepts, because she loves him.

Very soon, the couples get married and Zeno starts to realize that he can love Augusta. This surprises him as his love for her does not diminish.

However, he meets a poor aspiring singer by the name of Carla and they start an affair, with Carla thinking that Zeno does not love his wife. Meanwhile, Ada and Guido marry and Signior Malfenti gets sick. Zeno's affection for both Augusta and Carla increases and he has a daughter by the name of Antonia around the time Giovanni passes away. Finally, one day, Carla expresses a sudden whim to see Augusta. Zeno deceives Carla and causes her to meet Ada instead. Carla misrepresents Ada as Zeno's wife, and moved by her beauty, breaks off the affair.

Zeno goes on to relate the business partnership between him and Guido. The two men set up a merchant business together in Trieste. They hire two workers named Luciano and Carmen (who becomes Guido's mistress) and they attempt to make as much profit as possible.

However, due to Guido's obsession with debts and credit as well as with the notion of profit, the company does poorly. Guido and Ada's marriage begin to crumble and so does Ada's health and beauty. Guido fakes a suicide attempt in order to gain Ada's compassion and she asks Zeno to help Guido's failing company.

Guido starts playing on the Bourse (stock exchange) and loses even more money. On a fishing trip, he asks Zeno about the differences in effects between sodium veronal and veronal and Zeno answers that sodium veronal is fatal while veronal is not. Guido's gambling on the Bourse becomes very destructive and he finally tries to fake another suicide in order to gain Ada's compassion. However, he takes a fatal amount of veronal and dies. Soon thereafter, Zeno misses Guido's funeral because he himself gambles Guido's money on the Bourse and recovers three quarters of the losses.

Zeno relates his current life. It is during the time of the Great War and his daughter Antonia (who greatly resembles Ada) and son Alfio have grown up.

His time is spent on visiting doctors to cure his supposed imagined sickness. One of the doctors claims that he is suffering from the Oedipus complex, but Zeno does not believe it to be true. All the doctors are not able to treat him. Finally, he realizes that life itself resembles sickness because it has advancements and setbacks and always ends in death. Human advancement prolongs life and it is that which causes more sickness and weakness in humans. Zeno imagines a time when a person will invent a new, powerful weapon of mass destruction and another will steal it and destroy the world, setting it free of sickness.

89. Jonathan Swift, Ireland, (1667-1745), Gulliver's Travels

First Edition of Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels (1726, amended 1735), officially Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, is a novel by Jonathan Swift that is both asatire on human nature and a parody of the "travellers' tales" literary sub-genre. It is widely considered Swift's magnum opus and is his most celebrated work, as well as one of the indisputable classics of English literature.

The book became tremendously popular as soon as it was published (Alexander Pope stated that "it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery"), and it is likely that it has never been out of print since then.

George Orwell declared it to be among the six indispensable books in world literature. It is claimed the inspiration for Gulliver came from the sleeping giant profile of the Cavehill in Belfast.

The book presents itself as a simple traveller's narrative with the disingenuous title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, its authorship assigned only to "Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, then a captain of several ships". Different editions contain different versions of the prefatory material which are basically the same as forewords in modern books.

The book proper then is divided into four parts, which are as follows.

Part I: A Voyage To Lilliput

The book begins with a short preamble in which Gulliver, in the style of books of the time, gives a brief outline of his life and history prior to his voyages. We learn he is middle-aged and middle-class, with a talent for medicine and languages, and that he enjoys travelling. This turns out to be fortunate. Upon careful reading, this introduction proves to be one of the most satirical points in the book: laced with innuendos and other forms of ironic humour: a trademark of Swift's writing.

On his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and awakes to find himself a prisoner of a race of 6 inch (15cm) tall people, inhabitants of the neighbouring and rival countries ofLilliput and Blefuscu. After giving assurances of his good behaviour he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the court.

There follow Gulliver's observations on the Court of Lilliput, which is intended to satirise the court of then King George I. After he assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudans (by stealing their fleet) but refuses to reduce the country to a province of Lilliput, he is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded.